I think I can contribute a little bit to this because I am one of the—probably not too numerous—people who "design trills" for real instruments: When I arrange for crank and other mechanical instruments, I have to painstakingly lay out the separate notes that are played, with exact duration and speed. A little bit of this is explained here, but of course that text still assumes that there is a "human trill manufacturer." The extension of these thoughts to "automatic trill manufacturing" is the goal of this pamphlet.

An example

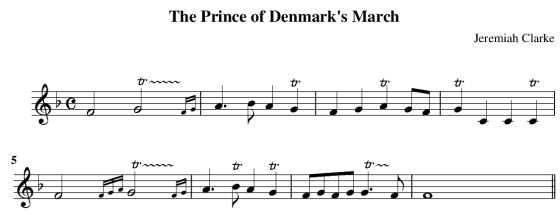

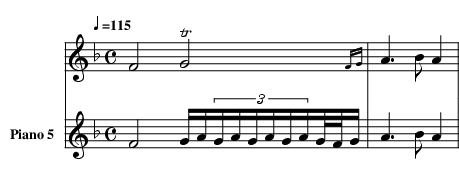

Before I try to say a little bit about my ideas of a trill's parameters, one should of course look at—and listen to—at least a few examples. To this end, I selected—for no particular reason—the beginning of Jeremiah Clarke's "Prince of Denmark's March" (also known as "Trumpet Voluntary") and ornamented it with nine trills. Here is the score:

The original score for harpsichord can be seen in this score on IMSLP on page 13 (the 18th page in the PDF). That score from the year 1700 contains, by the way, an interesting section "Rules for Graces" which I will completely ignore for reasons explained below.

I will "design" the first trill for Clarke's march in detail in the next section, but I'd like to present an, in my opinion, acceptable expansion of all the trills just to show how complex such simple trills may become. In a later section, I will explain for a few of these trills why I "designed" them as I did (clicking on the notes will play an MP3 file):

The scope of this discussion: Deciding on the note lengths, not the notes

My discussion (and algorithm) is concerned with assigning lengths to the notes that are played during trill so that the trill "sounds good."

I do not consider how these notes are "correctly selected." Especially, my discussion here is not (at all) about writing "historically correct" trills. In the piano example above, the notes in the trills above may or may not be acceptable for Jeremiah Clarke's march regarding our historical knowledge of trills in the 17th century (in this case, we know that the piano trills are definitely against the rules of the time, as these are laid out in the score as mentioned above). Rather, I assume that the performer has decided on the notes in the trill "according to her or his artistic taste" beforehand; and now has the problem to decide on the precise note lengths for each and every note in the trill so that they will create a "good sounding trill." This important step is usually ignored by texts on trills. It is often added as a footnote or in an appendix in scores either for beginners, or when "special trills" do occur. But virtually always, the descriptions given there are only very crude approximations to what is really played—almost always, all the notes in the various parts of a trill (the preparation, the shake proper, and the termination) are shown as being of equal length, which is usually wrong: A standard trill typically starts a little slow in the preparation, has a continuous speed in the shake, and finally either speeds up or slows down a little in the termination. Capturing these variations manually, and then algorithmically will be the topic of the next sections.

Working out a trill

Let me write out the first trill of this melody in single notes. For this, we have to select a few "structural" parameters:

- Should the shake of the trill (i.e., the two quickly alternating notes in the trill) start with the main note, or with an auxiliary note?

- What is the secondary note, or equivalently, what is interval of the shake?

- Should there be an explicit preparation, i.e., a non-trilling start?—this could be a longer holding note before the proper trill begins, or a short scale (2 or 3 grace notes) leading into the trill.

- What should the final notes—the termination—of the trill look like? Typical possibilities include again a longer note or a turn (playing once around the main note).

- There is no indication at all—the selection of preparation or starting note as well as termination is (thought to be) understood by everyone according to "well-known" rules.

- Grace notes indicate special wishes of the composer or arranger.

- Some other markings are used, e.g., a "turn" mark (lying S) near the "tr" indicating that the trill should end with a turn.

Here is a first attempt to expand this trill to thirtysecond notes. The turn at the end is a little slower than the trill (clicking on all subsequent score sections will start a corresponding MP3 file):

I am not at all happy with this: This is simply too fast.

Here is a second attempt with sixteenth notes and now a turn that is a little faster than the trill:

This one is definitely too slow.

Here is a third attempt, derived from the fast version, but this time with a somewhat slower preparation—maybe this "leads" the ear into the fast trilling:

Well ... the somewhat slower preparation does help a little, but the speed of the shake is simply too high.

The fourth version uses an intermediate triplet tempo. Again, the preparation is a little bit slower (normal sixteenths):

Now this sounds reasonable! Still, I'd like one more tweak: In the termination, I'd like to "slow down" a little. I do this by making the last note again a complete sixteenth. For compensation, two of the turn notes get even faster:

With much concentration, you might hear the small difference—an ordinary listener would probably not be able to distinguish the two versions.

More trills and some musical justification of their expansions

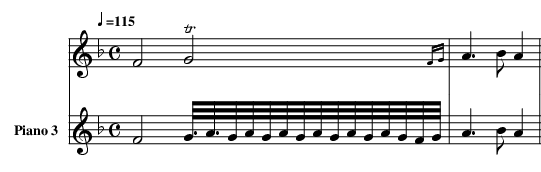

I have already shown an expansion of the 8 bars of Clarke's march at the beginning. Here are two more expansions of the trills, this time more in line with what we know about trill playing in Clarke's times insofar that the trills now start on the auxiliary note above the trill's main note. The first expansion is for a "lovely flute:"

Here are some thoughts on the design of the first trill: The slightly longer notes in the preparation and, even more so, starting the trill on the auxiliary note give the beginning of this trill a huge stress: We hear very distinctly that this note is important in some way. The fast shake is then actually somewhat relaxing. Even more so, the notes in the termination are again a tiny bit longer than the shake notes, reducing their "power" so that they "glide" into the following long note (in measure 2), thereby stressing that note. I am not quite sure how a trill can, at the same time, stress a note, but then stress the subsequent note even more: But this is evidently what happens here with the G in measure 1 and the following A in measure 2. Similar effects can be heard with the other longer trills.

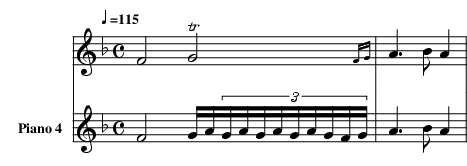

Here is another possibly expansion of the same trills, this time from (or for) a more "aggressive flute player:"

I do not know whether you like the "lovely flute" or the "aggressive flute" more—but certainly both are legitimate or at least musically possible expansions of the trills in the first score.

What can be seen from the scores—and has been explained somewhat more extensively in the previous section—is that a trill by no means consists of notes of equal length. Rather, the trill in itself needs a complex structure to give a satisfying musical experience. The question is whether one can create such "nice" or at least "acceptable" trills from only a few parameters, instead of painstakingly writing out all the single notes.

Parameters for playing a trill

The above trills were all hand-crafted by me, as a "benchmark" against which I could test automatically created trills. How can one create similar trills "from a set of rules," as is the case in a program? Obviously, the "structural parameters" mentioned above are always necessary:

- What is the trill's main note?

- What is the trill's interval?

- Is the starting note the main note of the trill or the auxiliary note?

- What are the notes of the preparation, if any?

- And what are the notes of the termination, if any?

- What is the length of a single note in the shake?

- For each note in the preparation and the termination, we need an additional factor relating the length of this note to the standard note length in the shake.

Automatic trill generation

I have written a small experimental Lua program that takes, as input, a "trill definition" containing the parameters given above. The output is a Noteworthy Composer clip that can be pasted into a score to have the trill played. You can download the commented source of the Lua program here; currently, it takes hardwired Lua structures as input and writes its result to the standard output via print.

Here is the definition of the first trill:

twoNotePreparationB2 = {

{ deltaPitch = 0, stretch = 1.3 },

{ deltaPitch = 2, stretch = 1.3 }

}

threeNoteTermination2 = {

{ deltaPitch = 0, stretch = 0.9 },

{ deltaPitch = -2, stretch = 0.9 },

{ deltaPitch = 0, stretch = 1.1 }

}

printTrillNotes({

zeroPitch = 71,

pitch = 67, -- g4

length = 1/2,

shakeNoteLength = 5/128,

shakeDeltaPitch = 2,

preparation = twoNotePreparationB2,

termination = threeNoteTermination2

})

The preparation and termination shown above are two of a set of standard preparations and terminations that work, in my opinion, well enough for standard trills. A user-friendly program (e.g. a Noteworthy Composer trill object!) would give the user the possibility to choose from a list of preparation and termination types as well as the basic speed of the trill (which defines the shakeNoteLength), and then try to find the various deltaPitch values by looking at the current key and surrounding accidentals; but give the user possibilities to override the pitches.

The program, as currently written, allows only for note lengths that are integral multiples of 1/128. Triplets are not possible: At first, I thought that triplet notes are necessary for nice-sounding trills. However, the difference between a triplet note and the multiples of 1/128 near it is so small that it is not perceptible. When manually writing trills, triplet notes help to keep the number of notes and of ties down; but with automatic note generation, one can hopefully ignore this issue.

Also, there is not yet a satisfying definition for prallers and mordents. Therefore, in the following scores, such trills are copied over from the manually written scores.

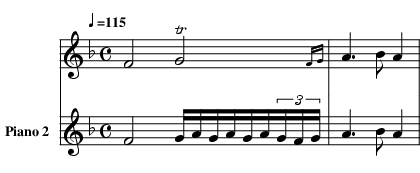

Here, now, are trills for "piano" and "lovely flute" in Clarke's march, generated from straightforward trill definitions (that are contained in the Lua file linked above):

I, for my part, find these trills as nice as my manual ones. And they are certainly nicer than trills without preparations and terminations.

(I leave the generation of trills for the "aggressive flute" as an exercise to the reader ...).

Some open issues

In order to claim that the parameters shown above are enough to get every trill to play satisfyingly, one would have to define and listen to many trills of different musical periods. I suspect that a few additional parameters might be necessary for the following features:

- It might be necessary to change the speed of the shake throughout the trill. Hopefully, a linear change of the speed (or the shake note length) is sufficient, but of course a "speed shape" consisting of a line graph describing multiple speeds and speed changes might be a better (but more complex) choice.

- Prallers and mordents have their own structure: There is a short trill of a selected speed, and then a longer note filling up the rest of the note length. A definition using a fixed length instead of a "stretch factor" might be better suited for these.

- Finally, a turn looks very much like a "trill without shake". Actually, I have defined the turn in measure 6 of my example score exactly like that—but it might be that a simpler structure, or at least a simpler user interface is more suited to describe a turn.

No comments:

Post a Comment